The chronic impact of high intensity training is unavoidable even when every possible control is implemented. And when I refer to high intensity, I’m not talking exclusively about failure training—anything that would be considered sufficiently stimulating (I.e. effective reps) is intense enough to warrant mitigation strategies. It’s not enough to track your RIR and RPE and listen to your body; your programming must be built with fatigue management in mind.

Anyone who has been coached by me understands my affinity for planned and structured deloads. Despite the baggage the concept carries and the vocal opponents’ vociferous strawmanning, there is no better way of controlling for the negative effects of sustained hard training while allowing for the propagation of the positive ones.

Before we go any further, it’s probably useful to go over what a deload actually is and why they’re useful:

A deload is a period (typically one training week but can be as short as 3-4 days) where the goal is to reduce systemic and local fatigue through reductions in volume, intensity, and relative load. They’re usually implemented after the culmination of a hard mesocycle and are meant to prepare you physically and psychologically for the next phase of training. In short, deloads are meant to be planned, easy training.

Most don’t like the last part of that definition…”easy”. And many would object to the abstract reference to “hard” training that a deload is meant to punctuate. But despite objections, there are clear markers that “hard” has been exceeded (at least acutely) and “easy” is necessary to facilitate continued progress.

Here are some signs I look for in my own training, and in my clients’ check-ins, to determine that a deload is the best course of action moving forward (skip this section if you’ve read Training, Explained):

Excessive DOMS

When soreness indicators are becoming excessive and constant after bouts of training, it is generally a sign that recovery capacity has been exceeded and a deload is needed to wash the fatigue out before attempting to push back up again.

Performance Plateau or Regression

The goal of overloading training is quite literally meant to overload or “do more” than the last bout. Doing this frequently and long enough will add up to more muscle growth. However, this is not sustainable linearly or indefinitely. At some point, we will experience a halt in progress and, in some cases, we will see performance markers actually go backwards if fatigue is high enough and remains unaddressed. If this is notable for 2 training weeks in a row across multiple sessions, it is time to deload.

Chronic Sickness

This should go without saying but having a sickness or ailment that just “won’t go away” is a very clear sign of a compromised immune function and one of the biggest contributors to this is a summation of hard training. Random stomach bugs and head colds are inevitable but if you find yourself constantly struggling to kick even the simplest of symptoms, like a cough, it may be time to pull back on training for a while and allow your body to fully recover.

Aches and Pains

To a degree, this is going to be unavoidable when you are training hard no matter how intelligent you go about programming and planning, but the compounding achy joints and strained muscles can be a clear indication that too much of SOMETHING is being done in the gym and not enough of everything else is being done to accommodate that training. If you find yourself accumulating nagging injuries at an accelerated rate, think about tapping the breaks for a bit and allowing those to heal before they set in and become chronic issues.

Life Events and Travel

Training is always secondary to enjoying life even for the most serious competitors and eventually, things will be scheduled that necessitate a leave of absence from the gym. If we have some forewarning, we can plan training to crescendo right before the leave so that we can use this event/travel/vacation as a deload.

Once we come to the conclusion that a deload is necessary based on one of (or multiple) the factors above, the next step in the process is to figure out how exactly we should go about implementation as there are a few ways we can go about it:

Combined Reduction

This will be the method that is most effective for dropping accumulated fatigue while also maintaining training qualities, like technical aptitude, and stimulating further recovery through increased blood flow and ROM. For this, we recommend tapering volume significantly, by 40-50%, and intensity moderately, by about 25-30%, from the last overloading training week before implementing the deload.

For example:

Week 1: Squats 2×8-10 (4RIR) with 100lbs

Week 2: Squats 3×8-10 (3RIR) with 1005bs

Week 3: Squats 4×8-10 (2RIR) with 110lbs

Week 4: Squats 5×8-10 (1RIR) with 115lbs

Deload: Squats 3×7 with 80lbs

Load Reduction

Though load on the bar is still a distance behind volume as it pertains to its ability to accumulate fatigue, combining high relative loads, as a % of 1 rep max (RM), with high relative intensities as a proximity to failure, will put a ton of stress on our local and global systems. When most people talk about deloading, they typically are referring to the load reduction method because “lighter” is used as a blanket term for this period.

For example:

Week 1: Squats 2×8-10 (4RIR) with 100lbs

Week 2: Squats 3×8-10 (3RIR) with 1005bs

Week 3: Squats 4×8-10 (2RIR) with 110lbs

Week 4: Squats 5×8-10 (1RIR) with 115lbs

Deload: Squats 5×8 with 50lbs

Volume Reduction

Volume will be the biggest contributor to fatigue, so it should generally be the variable that we attack first to reduce it. This can be done through a reduction in total sets, reps per set, or a combination of both.

For example:

Week 1: Squats 2×8-10 (4RIR) with 100lbs

Week 2: Squats 3×8-10 (3RIR) with 1005bs

Week 3: Squats 4×8-10 (2RIR) with 110lbs

Week 4: Squats 5×8-10 (1RIR) with 115lbs

Deload: Squats 3×5 with 100lbs

Modified Hypertrophic

Though the combined reduction of volume and load leads to the best specific outcomes with regards to dropping fatigue and preparation for the next mesocycle, employing what we like to call a “modified hypertrophic” deload typically lends a bit better to long-term outcomes when the goal is STRICTLY muscle gain. This still has elements of decreased volumes and loads to drive the recovery process but with the added element of increased voluntary contraction. In other words, we want to focus more heavily on the MM connection now that volume and load are no longer driving the intensity level.

For example:

Week 1: Hip Thrusts 2×8-10 (4RIR) with 100lbs

Week 2: Hip Thrusts 3×8-10 (3RIR) with 1005bs

Week 3: Hip Thrusts 4×8-10 (2RIR) with 110lbs

Week 4: Hip Thrusts 5×8-10 (1RIR) with 115lbs

Deload: Hip Thrusts 4×6 but the weight is autonomously chosen so that the athlete can perform the movement with the best execution and greatest perception of sensation in the glutes.

Time Off

This would be a period of completely taking off from strength training in lieu of a structured deload. Low intensity cardio can still be performed, and is recommended, but it is advised to steer clear of the gym fully during a planned time off to accommodate the psychological recovery (burnout) as well as physical. We do not recommend this more frequently than 2-3 times a year, but implementing at least one consecutive 7–10-day active rest is probably a very good idea.

I understand that this is a lot to take in and probably feels like an overkill, but it cannot be emphasized enough just how crucial periodic and planned reductions in training intensity (and volume) are for long-term progress. The dismissive hand-waiving of deloads as a beneficial tool for the hypertrophy athlete is the epitome of “losing sight of the forest for the trees” that is all too prevalent within certain circles (notably, the Cult of Intensity). These camps put forth the supposed counter-argument that “the body will you when you need a deload” as if that is in any way incongruent than the multitude of points I’ve made above. However, where their argument falls flat is the same place that I have decided NOT to hitch my wagon (as alluded to with respects to auto-regulation): on the naively optimistic assumption that human nature can be trusted. The anti-planned-deload crowd wants to believe that people will always be honest in their reporting and accurate in their subjective biofeedback tracking and not fuck everything up. Unfortunately, I’ve never been able to believe this fairy tale…Call me a pessimist, I guess.

Deloading isn’t about looking for an “easy way out” or trying to avoid “doing the hard shit” or whatever other nonsense argument gets spun by detractors. It’s based primarily on an understanding that humans are fallible, and this fallibility has to be controlled for even if the resulting approach is overly conservative at times.

I’d rather deload too early than too late. And I’d rather deload too frequently versus not enough. At worst, the former leaves some gains on the table. However, the base case for the latter is burnout, injury, and dysfunction. As a coach, it seems pretty clear which trade-off I’m willing to make for my clients.

Ok, let’s move on from deloads (you’re welcome) and talk about a couple of programming strategies that can be used to further mitigate and control for the inevitability of rising fatigue with progressive training:

First up, we have the intra-mesocycle increase of relative intensity from week to week. In lay terms, the idea is to start a new training block conservatively in terms of proximity to failure (i.e. ~3-4RIR) and gradually push closer to 0RIR over subsequent weeks. At it’s most simple application, the program would start at 4RIR for Week 1 then progress to 3RIR (Week 2), 2RIR (Week 3), 1RIR (Week 4), and then culminate at 0RIR (or failure) during Week 5, which would be followed by a deload.

Obviously, we can imagine scenarios in which this way would be suboptimal or even contraindicated—Would we want to start at 4RIR for a DB Lateral Raise? Would we want to end with 0RIR for a Barbell Goodmorning? Would we want to progress like this for a non-overloading movement such as a Cable Glute Kickback (in which, the intent is specified to be improvement of the mind-muscle connection)? Would we want to linearly decrease RIR each week for a novel movement that needs technical practice?

The answer lies in establishing a principle of progression loosely based off this strategy but biased towards the middle-ground and edge cases. Intensity, load, and/or reps don’t have to be added every single week if the entire program is slowly shifting from less intense, heavy, and voluminous to more. Pushing the training along a defined path allows for estimated timelines to be established and deloads to be planned, even if modifications are made at times. Extrapolating out, this means that starting and ending a training block in the same spot runs counter to this staged, deliberate, and, at times, forced approach to progression; whether the start and end points are at failure or 5RIR won’t change the argument here. Jumping into a new program all gung-ho and pushing the intensity too hard too fast (like with going to failure right out of the gates) will artificially cap any progressions that might have been possible with a more titrated approach. Conversely, starting out conservatively (maybe even a bit easy) and easing into the training over the course of several weeks, allows for momentum to be built, confidence to be established, and real progressions to be made in terms of sustained hard training.

Now that we have our plan outlined for how to approach our microcycles within each block, we need to figure out what to do at the next level up: mesocycles.

Despite what you may have heard, sticking with the same program for exorbitant amounts of time (no matter how good or close to optimal it may be) is probably a poor idea for most people. Outside of beginners and those who are able to make slow, continuous gains from moderate intensities and volumes (think detrained athletes and those recovering from injury), most trainees need some degree of evolution built into their programming. This can come in all shapes and sizes ranging from the nearly imperceptible (volume titrations) to the drastic (phase changes between blocks). But understand that while it might be slightly dramatic to say “evolve or die” is a paradigm worth applying here, it’s also not completely incoherent.

I often defer to a simple analogy to explain the concept of phase potentiation:

Imagine you have a button that controls your muscularity. At first, the sensitivity is profound, and every time you press this button, you see immediate feedback in terms of more muscle and added strength. But over time, you start to notice that the button isn’t working as well as it did before. Now you’re pressing it harder and more frequently just to get the same, if not less, of a response. Until eventually the button becomes worn out and ineffective, yielding nothing no matter what you do. But what if you could replace that button and patch up all the old wiring and circuitry to go back to what it was like before?

Physiologically speaking, that’s actually possible through strategic use of phase shifts throughout a macrocycle (I.e. between mesos)! But how?

Let’s flip the analogy back to training and hypertrophy:

That button is akin to training—the impudence that creates the desired effect. And just like our button eventually wore out, so does our hypertrophic response to resistance training. And just like we can replace the button and refresh its components, we can resensitize our bodies to growth by periodically rotating the focus of our training and the primary pathways we use to achieve it.

In some respects, this is obvious, intuitive, and something we do without even thinking about it. Variation in exercises, rep ranges, sequencing, tempo, and even rest periods are all ways in which we can subtly refurbish our hypertrophic buttons. These are variables that most trainees already adjust pretty frequently even if it’s not with the explicit goal of potentiation. And that’s a great start! But when you get to a certain level of advancement, things don’t tend to happen by accident…More must be done.

When training, do you think about which mechanism of hypertrophy you’re biasing? Are you aiming for mechanical tension? Or metabolic stress? Or muscle damage? Or maybe something tangential like trying to improve your work capacity? And when programming, do you look at how different systems can be maximized, minimized, or supplemented throughout the macrocycle? And when planning your macrocycle, do you think about how short-term goals can often strategically deviate from the long-term goals but still end up a more optimal strategy?

I apologize if I feels like I’m speaking in code here but these are all very tangible ways in which we can think about breaking our training down into constituent parts to create something greater than the sum. Phase potentiation is just a fancy way of saying that we structure the programming (specifically, the meso to meso design) in a way that allows the blocks to amplify their effects. While more progress is certainly nice, it’s actually the attenuation of stagnation that is the really big deal here.

If we can build our training in a way that undulates intensity, volume, frequency, exercise section, and other variables in order to properly manage fatigue and prevent physiological down-regulation, we can effectively train hard year-round with minimal risk of injury or burnout while maximizing rate of growth.

Pulling it all together:

1. Intra-mesocycle intensity progression:

• Start a training block conservatively (3-4 RIR)

• Gradually increase intensity over weeks (4RIR → 3RIR → 2RIR → 1RIR → 0RIR)

• Follow with a deload week

• Adapt this strategy based on exercise type and individual needs

2. Progress gradually:

• Allows for momentum building

• Establishes confidence

• Enables real, sustained progress

• Avoids artificial caps on progression caused by starting too intensely

3. Evolve your program over time:

• Sticking to the same program long-term is often suboptimal

• Most trainees need some degree of change in their programming

• Changes can range from subtle to drastic

4.Methods of implementing variation:

• Rotating exercises, rep ranges, sequencing, tempo, and rest periods

• Considering different mechanisms of hypertrophy (mechanical tension, metabolic stress, muscle damage)

• Balancing short-term and long-term goals in programming

5. Phase potentiation:

• “Replace the worn-down button”

• Involves strategically shifting training focus between mesocycles

• Helps resensitize the body to growth stimuli

6. Benefits of phase potentiation:

• Amplifies effects of individual training blocks

• Attenuates stagnation

• Allows for year-round hard training with reduced risk of injury or burnout

• Maximizes growth rate through strategic undulation of training variables

7. Take a holistic approach to programming:

• Consider how different systems can be maximized, minimized, or supplemented throughout the macrocycle

• Structure mesocycle-to-mesocycle design for optimal long-term results

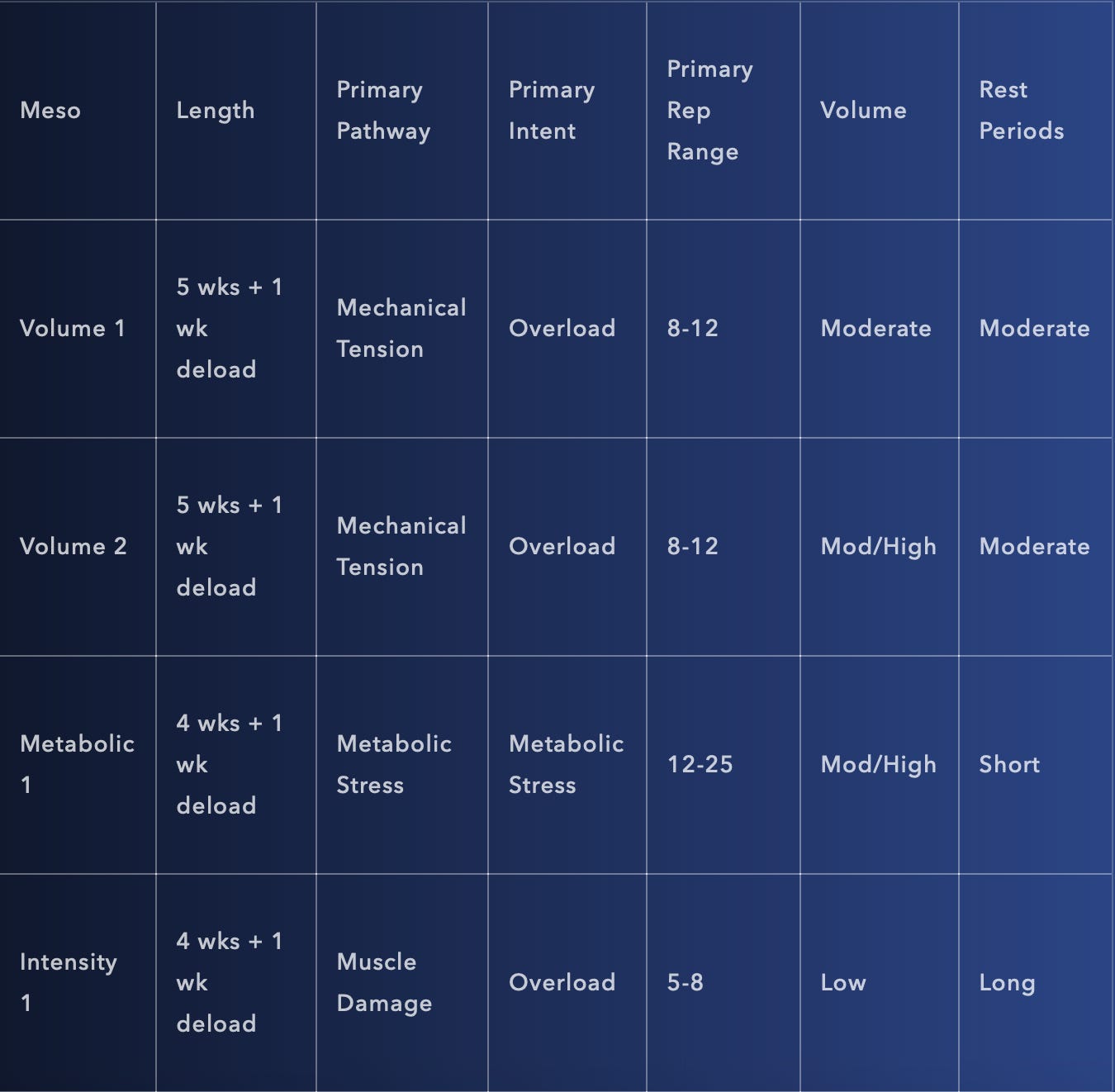

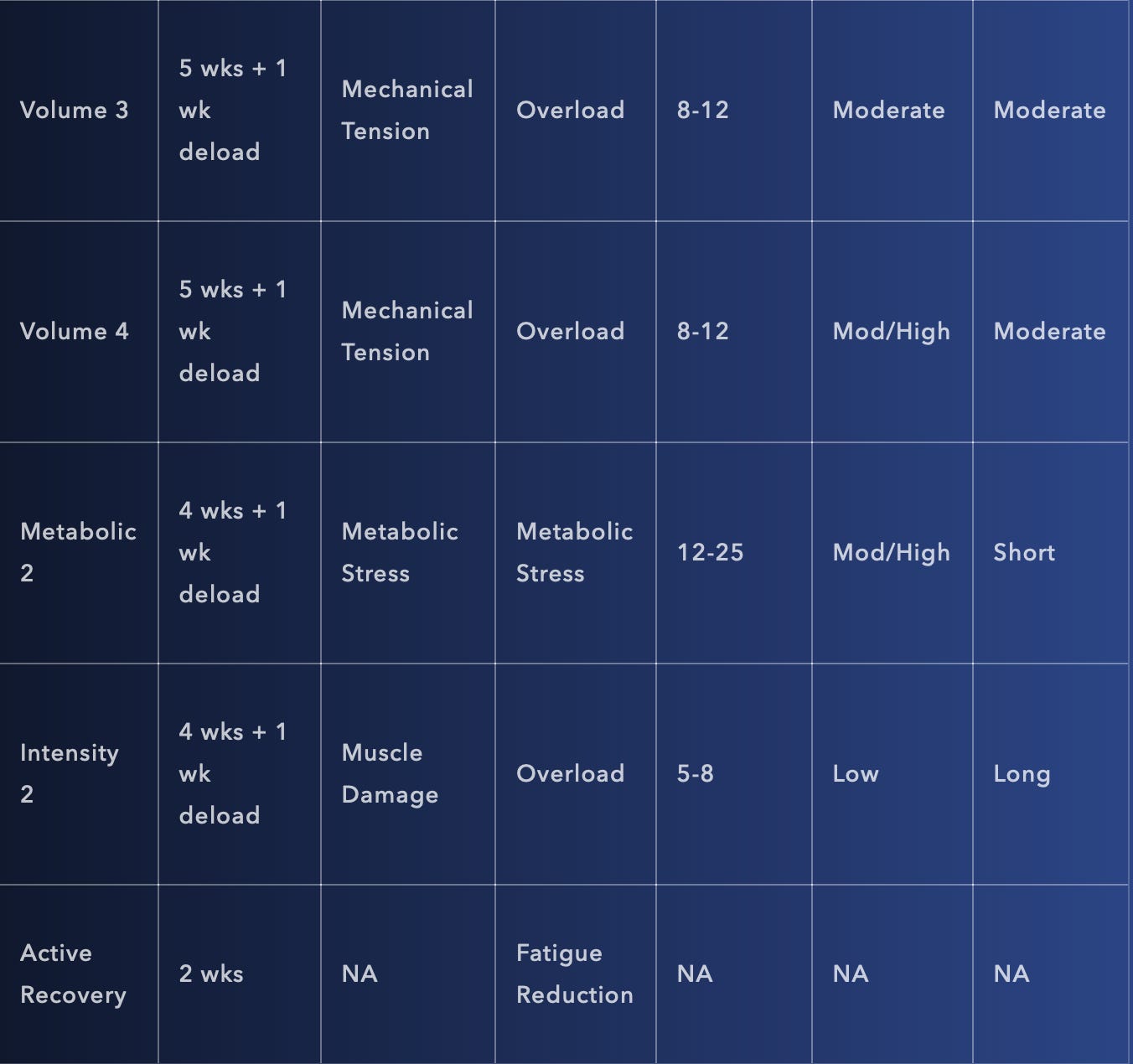

I know this seems too good to be true but let’s take a walk down this path and see how this could be implemented in practice:

As you can see from the table above, the mesocycles are meant to complement one another. They’re ordered strategically so that the qualities developed in the previous meso carry into the new one and allow for a higher starting point than would be possible otherwise. When transitioning into a metabolic block, for example, the constant pressing on the overloading/mechanical tension button gets a break in favor of a more novel route towards that same hypertrophy. And even though metabolic stress isn’t nearly as effective at building muscle as mechanical tension, the shift allows us to kill two birds with one stone: giving our overload pathways time to recharge as well as stimulating potentially untapped (or at least, neglected) gains.

Pulling it back around, I’d like to make note of the “intensity” blocks, specifically. The classification is vague on its own, but for me, these are meant to be phases where failure training is implemented more liberally, though still strategically and in line with the greater macro.

Intensity techniques can even be thrown in the mix at this point. This is the block to go for broke, try to eclipse those rep PRs, and make the Cult of Intensity proud. Now, you’ll notice that this type of mesocycle rolls around once every 4ish blocks (which equates to about 6 months) as it’s presented here. It’s not that failure can’t be implemented more regularly than this, but doing so at this level, within these progression models, and as the culmination of previous overloading training, necessitates scarcity and extremely deliberate, if not hesitant, implementation.