But all hope for training hard isn’t lost. Just because our systems have built-in restrictor plates that put a soft ceiling on our physical abilities doesn’t mean that we have to accept those limitations at face value. In fact, we don’t have to outsmart biology in order to train harder for longer—all that’s needed is a bit of critical thinking and strategy…

And the simplest place to strategize from is one which places controls on intensity to allow titrations up or down in accordance with recovery and other extrinsic circumstances.

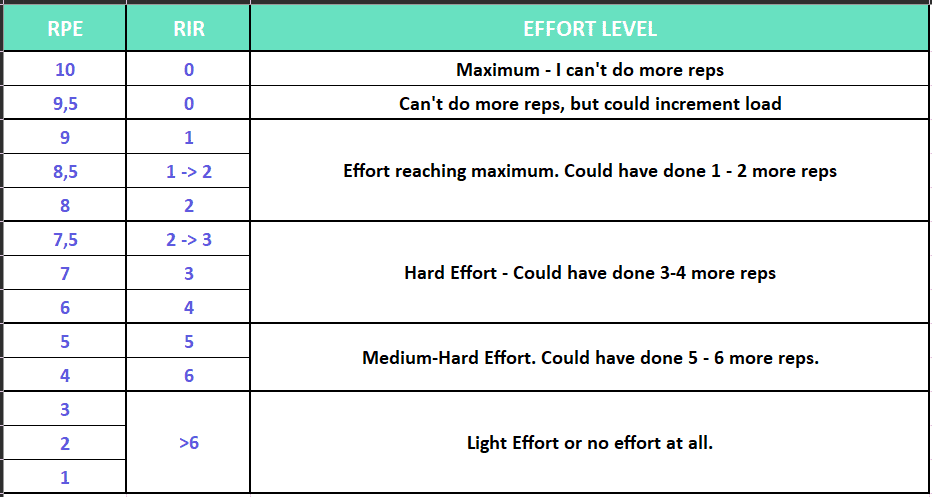

There are two primary methods for modulating intensity: RIR and RPE.

Reps In Reserve (RIR) is meant to be an objective measure of how close you are to failure. In other words, how many reps away from failure you are at any given moment should be able to be assigned a value. And that value would be the RIR. Therefore, taking a set to 0RIR would be the same as taking a set to failure. Almost all worthwhile training will live between 0-4 reps in reserve, with anything less intense being insufficiently stimulating and anything more being beyond the realms of sustainability (even the most ardent members of the Cult of Intensity would agree with this).

I’ve alluded to this concept of RIR in previous sections (such as when talking about effective reps), but those allusions did not give necessary dues to just how impactful this concept can be. The ability to intuitively understand how close you are to failure at all times is potentially the greatest skill a trainee can acquire. But as I’ve also alluded to in previous sections (when discussing the merits of failure training), integrating RIR into your programming as a guide can be stressful, confusing, and even counterproductive for those that cannot accurate judge their intensity. The objectivity of RIR is both a blessing and a curse—as being able to manage fatigue accurately in terms of proximity to failure is undoubtedly a powerful tool, but that tool loses its effectiveness rapidly when accuracy and precision are diminished.

In conjunction with RIR, we also have Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) which is a subjective estimation of intensity and effort. Note the intentional use of terms here: objective versus subjective. The implication is that RPE isn’t meant to be perfectly accurate or even reasonably gauge your proximity to failure. Rather, it’s just a measure of how hard you feel like you’re working. That’s it. And that simplicity is a feature that clearly draws the line in the sand between the utility of RPE compared to that of RIR.

In other words, when you want accuracy, use RIR. And when you want to defer to real-time biofeedback, use RPE.

I’m going to attempt to shy away from injecting my opinion on which I prefer…But I will say that, anecdotally, RIR seems to be more useful when goals are more closely aligned towards hypertrophy, and RPE seems to be similarly useful for strength and power training. Personally, I use both religiously in the programming that I write as I find each to be invaluable tools independently.

The best advice I can give to a beginner or intermediate trainee who is trying to establish good habitual practices is to pay attention to what you’re feeling as you approach failure points. Listen to the feedback your body is giving you. Track your training and accumulate quantitative and qualitative data over time. Learn how to use RIR and RPE in your training—trust me when I say that this is invaluable.

As we used RIR as a launchpad into RPE, it’s prudent to use RPE to push us forward into the final (common) way in which intensity and fatigue are managed: auto-regulation.

At the risk of sounding condescending, auto-regulation is literally the process of self regulating as you go. In some ways, it’s the culmination of mastering RIR and RPE in which both tools are used loosely to inform how training should go, but ultimately, planning and structure can be scrapped and an audible called based on biofeedback in the moment. Relying on auto-regulation as a foundational progression model is strictly for advanced trainees, and even then, very few individuals will actually be able to get away with “going by feel”. The reason for this should be obvious to anyone who has made it this far: our bodies don’t want to be pushed outside of their comfort zone and being homeostasis. Why a method like training to failure all the time can actually work so well in practice makes sense when overlaid on top of this backdrop. And auto-regulation assumes that the trainee can consistently and intelligently override their body’s natural emergency brakes to continue to push it to do the things it really doesn’t want to do.

While I think this methodology has merit and can potentially even be the best way for certain (advanced) athletes to train, I don’t trust human nature enough to expand my programming ideology to include vast reliance on auto-regulation. In specific circumstances and at certain times, I’m comfortable leaning into the benefits while controlling for the inescapable drawbacks. But in my humble opinion, the bulk of any good program should be rooted in the principles espoused by RIR and RPE.