Metabolic Stress: The intent is to stimulate blood flow to the target muscle, generating a build-up of cellular metabolites (i.e. lactate, H+, IGF-1, etc). This leads to the burning sensations that we know as the “pump” and, hopefully, sarcoplasmic hypertrophy. The load (and load progressions) are much less important here compared to volume density—relative intensity (i.e. proximity to failure) will still need to be high. Rep ranges will generally be higher than that of overload (in the 15-30 range) though this is not always a prerequisite to increasing metabolic stress; total time-under-tension is more important. Rest periods will be much shorter to intentionally prevent a full return to baseline between sets (i.e. ~30-60 sec). Despite using lighter loads and less systemically-taxing movements, fatigue and desensitization can quickly become problematic with continuous use of metabolic work. Exercises with few dependencies and high specificity should be selected. Though metabolic stress plays a part in any complete training protocol, it’s important to remember that over-emphasizing the “pump” in lieu of progressively overloading will quickly stagnate progress. Metabolic stress is most effective when implemented as a small percentage of volume (i.e. ~10-20%), or in dedicated mesocycles as part of a phasic approach.

Due to many of the same dependencies related to glute training that we’ve already discussed, targeted metabolic work will have to be extremely specific in order to maximize the effect. Compared to some simpler muscle groups, the glutes’ functions are intertwined and inseparable from that of multiple other muscles and systems, which makes isolation relatively challenging. Additionally, the multi-planar movement of the hip joint further convolutes efforts to partition tension in the glutes, and only the glutes.

Shorter rest periods with metabolic work means that many of the most stimulative glute movements will be contraindicated due to higher risk of injury. Barbells should generally be foregone for safer modalities, such as DBs, Smith machine, and cables. Axial loading should be limited as much as possible. Single leg variations should be used much more liberally, though the impacts of this shift on volume and fatigue should be carefully considered here. Interestingly, novelty can much more readily be used as a strategic tool with metabolic work. Specific intensity techniques—such as supersets, giant sets, myoreps, load drop sets, cluster sets, marathon sets, and pre-exhaustion—can be used to great efficacy.

Horizontal hip extension variations (i.e. hip thrusts, glute bridges, etc) are probably going to be the most effective here because of the more isolated nature of the tension. These movements can be taken close to failure—with high reps and in heightened states of fatigue—without haphazardly increasing the risk of injury or being limited by ancillary points of failure. Additionally, high-rep walking lunge and split squat variations (performed with a glute bias) can be incredible lengthening counterparts to the shortening of the horizontal hip extensions.

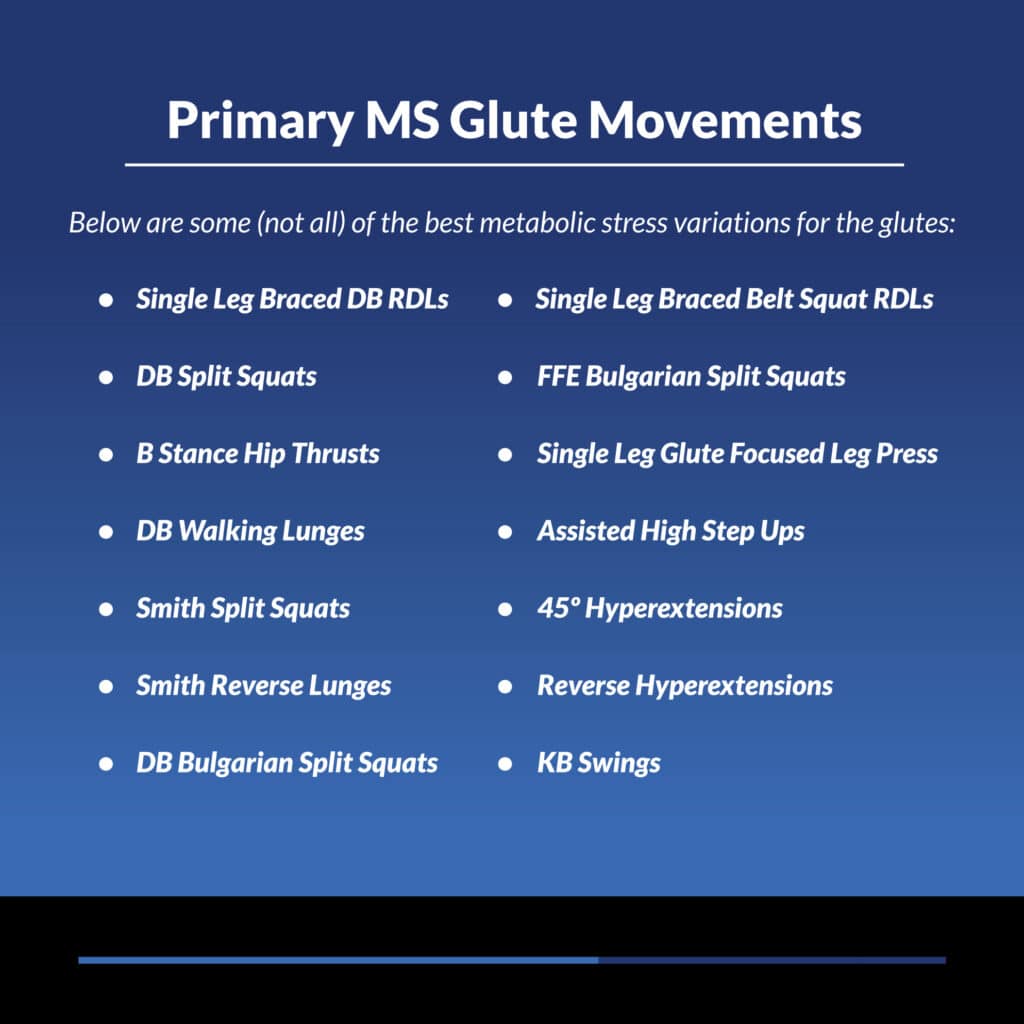

Below are some of the best metabolic stress variations for the glutes:

Smith Reverse Lunges

DB Bulgarian Split Squats

Single Leg Glute Focused Leg Press

Single Leg Braced Belt Squat RDLs

*Note: Not everyone will respond in the same way to the same specific exercises, or even movement patterns. For that reason, it’s crucial to experiment with different variations, modalities and execution variables in order to find those that best suite your individual anatomy, strengths and limitations. Keep track of objective data and subjective biofeedback in order to make unbiased exercises selections.