Despite the oceans of information bombarding us daily on this new glute exercise or that new glute program, building a pair of envy-inducing butt cheeks comes down to the same principles of progression that drive hypertrophy for every other muscle in the body: doing hard stuff for a long time. Actually, it’s more nuanced than that alone—we also have to ensure that the hard things we’re doing are outpacing the rate at which our glutes can adapt to the stimulus. In other words, progressive overload must be the primary driver of long-term glute growth.

That this is the raw reality underlying all of the distraction and fluff should come as no surprise to those who understand how the process of muscle growth occurs. So then why do so many intelligent, experienced, and in many cases, well-developed athletes fall for the same traps when it comes to glute training? My guestimation is that many trainees (especially women) are looking for some secret-sauce to attaining those attention-grabbing, algorithm-hacking, IG-model buns. It’s easier to speculate that there must be something we’re missing, something we’re not doing, something that would be the missing link if discovered. But the unfortunate and unsexy truth is that, outside of those blessed by Aphrodite herself, the path to a head-turning derriere inevitably must go through slow, monotonous, painful, and meticulous training.

I say all of this as a preface to this section, not as a turn-off or to be pessimistic, but to prepare you for what a truly effective and efficacious progression model for the glutes looks like. There won’t be any magic or reinventing of the wheel. The secret-sauce is the ability to withstand the weeks, months, and years of doldrums, yet continue to add load, add reps, and stick to the plan without succumbing to the tidal wave of distractions attempting to pull you off course.

So let’s look at some examples of progression models, at different levels, that can be used to grow your glutes:

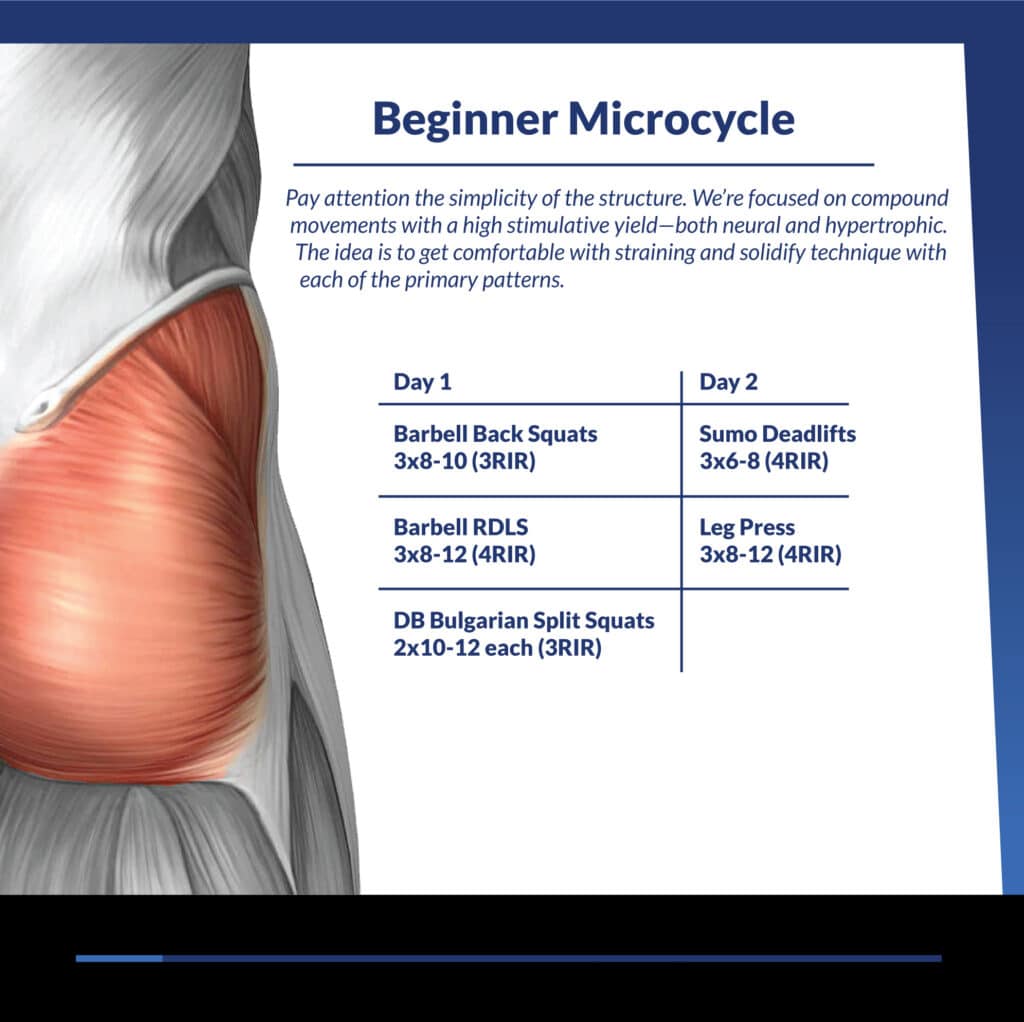

Beginner Microcycle

Pay attention the simplicity of the structure. We’re focused on compound movements with a high stimulative yield—both neural and hypertrophic. The idea is to get comfortable with straining and solidify technique with each of the primary patterns.

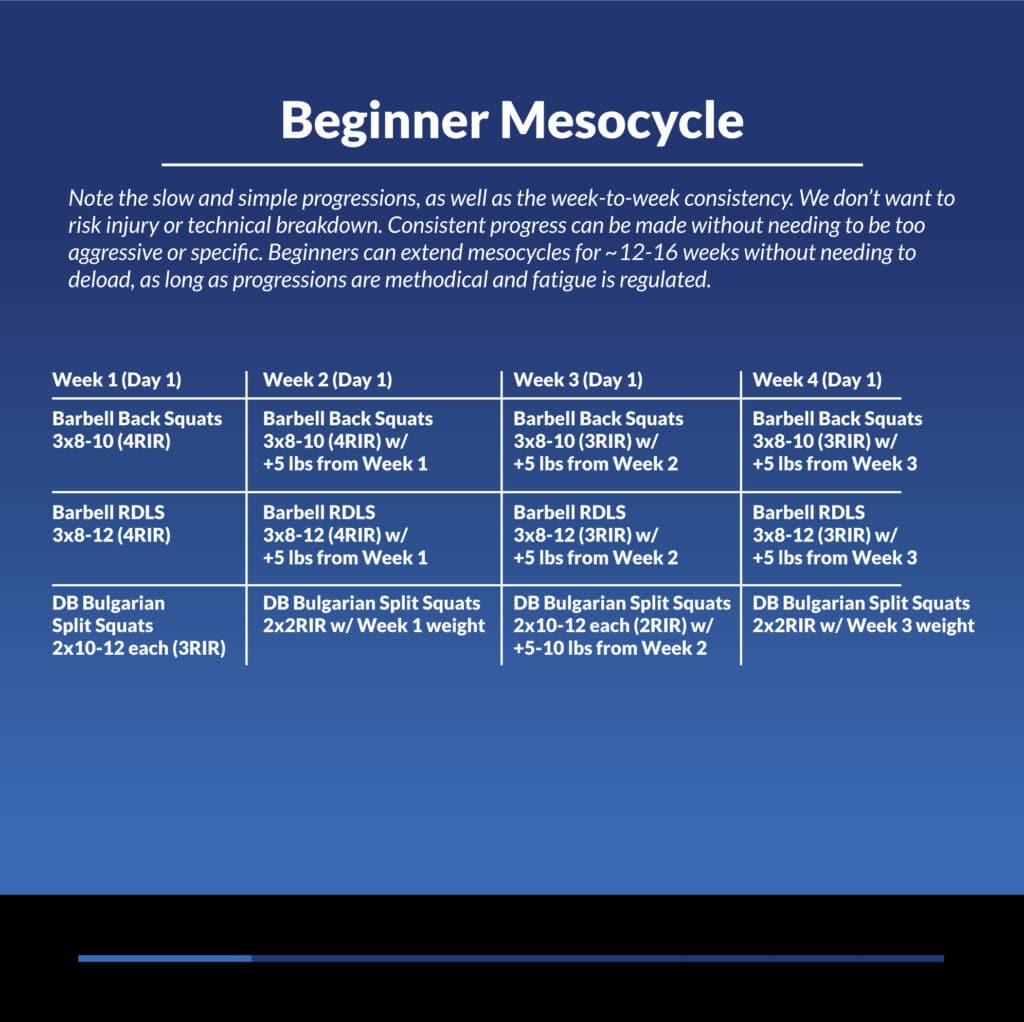

Beginner Mesocycle

Note the slow and simple progressions, as well as the consistency, from week-to-week. We don’t want to push too close to failure and risk injury or technical breakdown. Consistent progress can be made at this stage without needing to be too aggressive or specific in the approach. Beginners can extend mesocycles for ~12-16 weeks without needing to deload, as long as progressions are methodical and fatigue is regulated.

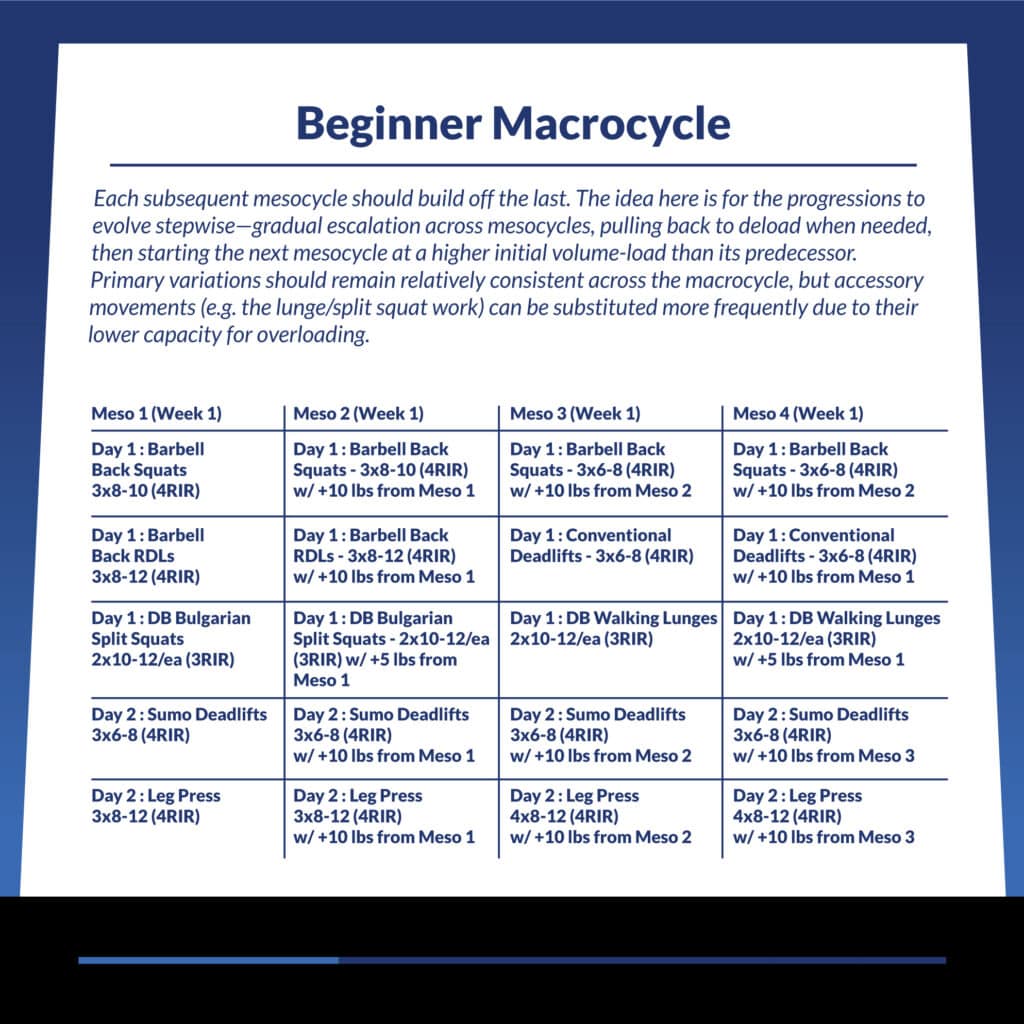

Beginner Macrocycle

The trend that we observed within beginner mesocycles will extend to the macrocycle design as well. We’re using each subsequent mesocycle to build off the last. The idea here is for the progressions to evolve stepwise—gradual escalation across mesocycles, pulling back to deload when needed, then starting the next mesocycle at a higher initial volume load than its predecessor. Primary variations should remain relatively consistent across the macrocycle, but accessory movements (e.g. the lunge/split squat work) can be substituted more frequently due to their lower capacity for being progressively overloaded.

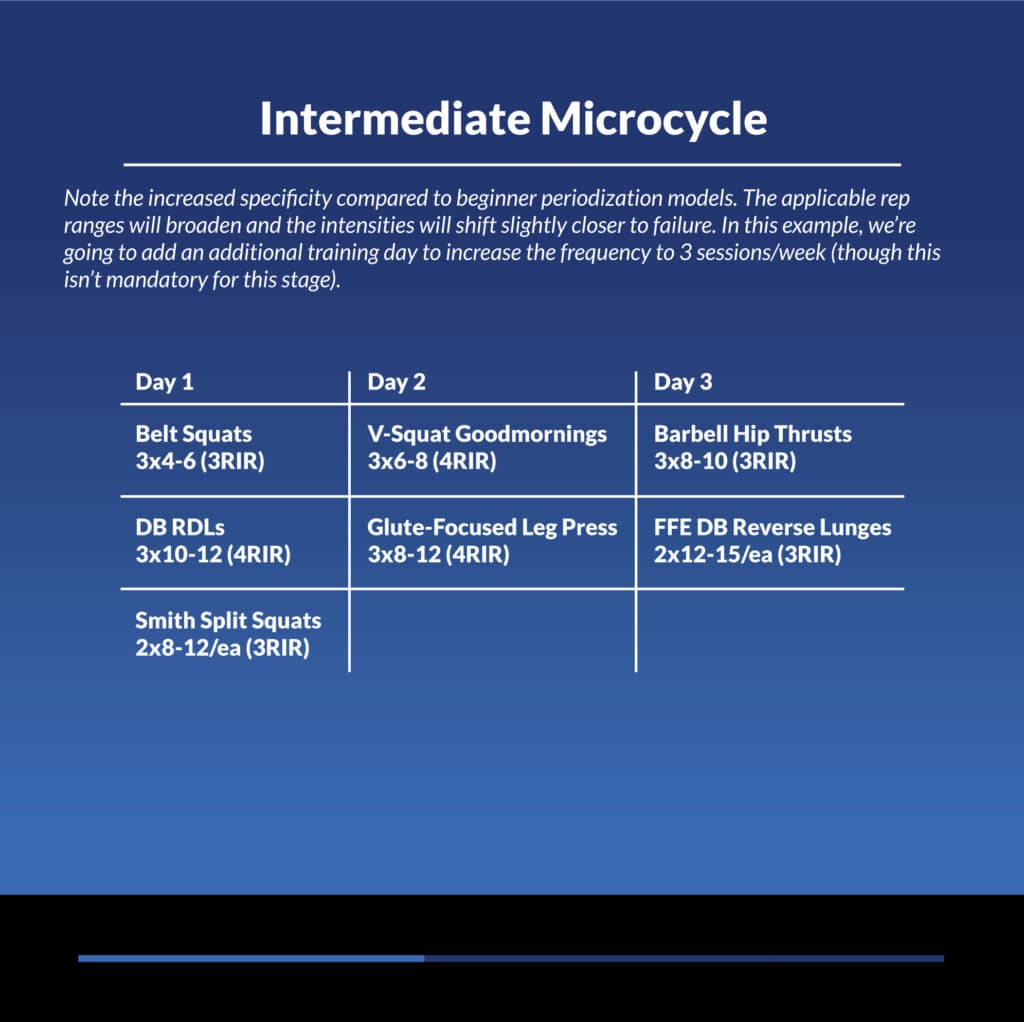

Intermediate Microcycle

Note the increased specificity compared to beginner periodization models. The applicable rep ranges will broaden and the intensities will shift ever so slightly closer to failure. In this example, we’re going to add an additional training day to increase the frequency to 3 sessions/week (though this isn’t mandatory or universal for the intermediate stage).

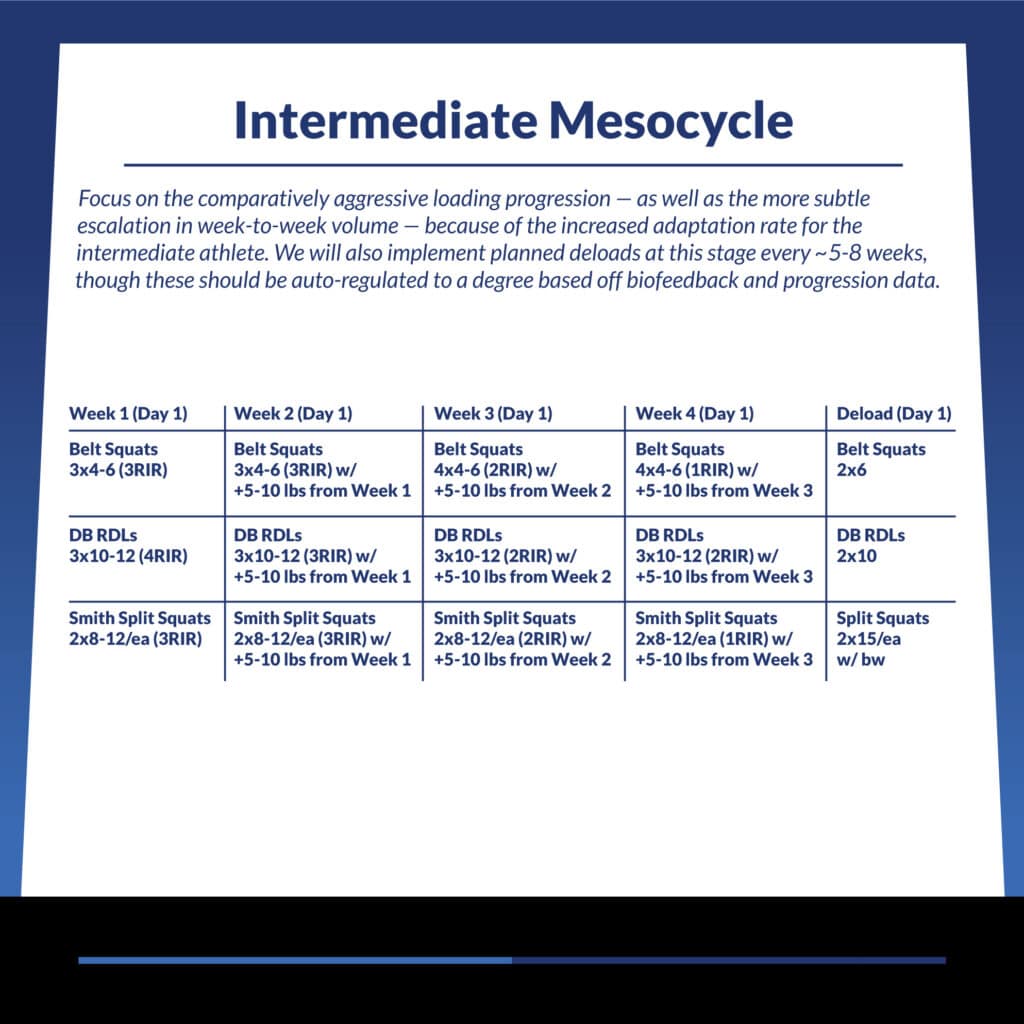

Intermediate Mesocycle

Focus on the comparatively aggressive loading progression, as well as the more subtle escalation in volume from week-to-week. This is necessitated by the more rapid rate of adaptation for the intermediate athlete. We will also implement planned deloads at this stage every ~5-8 weeks, though these should be auto-regulated to a degree based off biofeedback and progression.

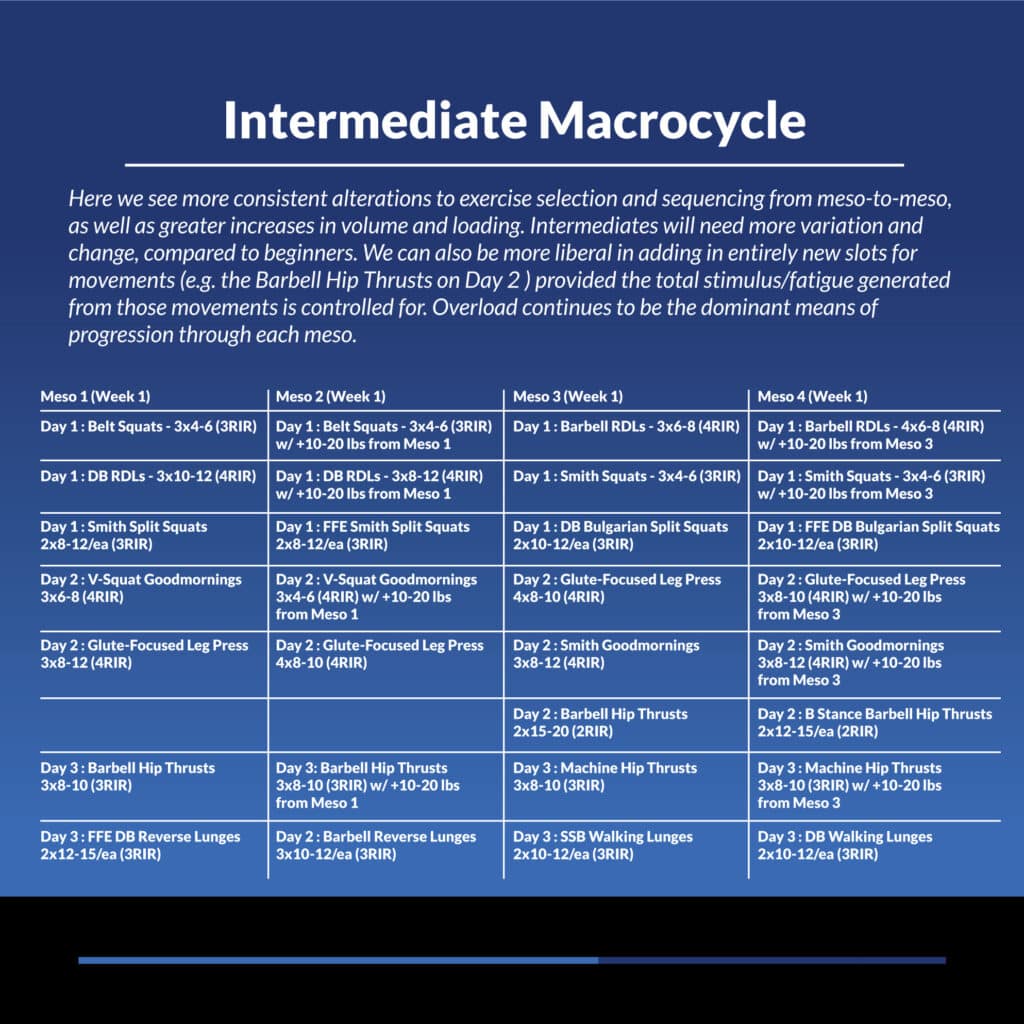

Intermediate Macrocycle

Here we see more consistent alterations to exercise selection and sequencing from meso-to-meso, as well as greater increases in volume and loading. The ability for intermediates to carry overloading progressions on the same exercises for multiple mesocycles in a row is going to be limited, thus the need for more variation and change. We can also be more liberal in adding in entirely new slots for movements (as we did on Day 2 with the Barbell Hip Thrusts) provided the total stimulus/fatigue generated from those movements is controlled for (i.e. we wouldn’t want to haphazardly add in Sumo Deadlifts because of its magnitude of disruption). Overload continues to be the dominant means of progression through each mesocycle.

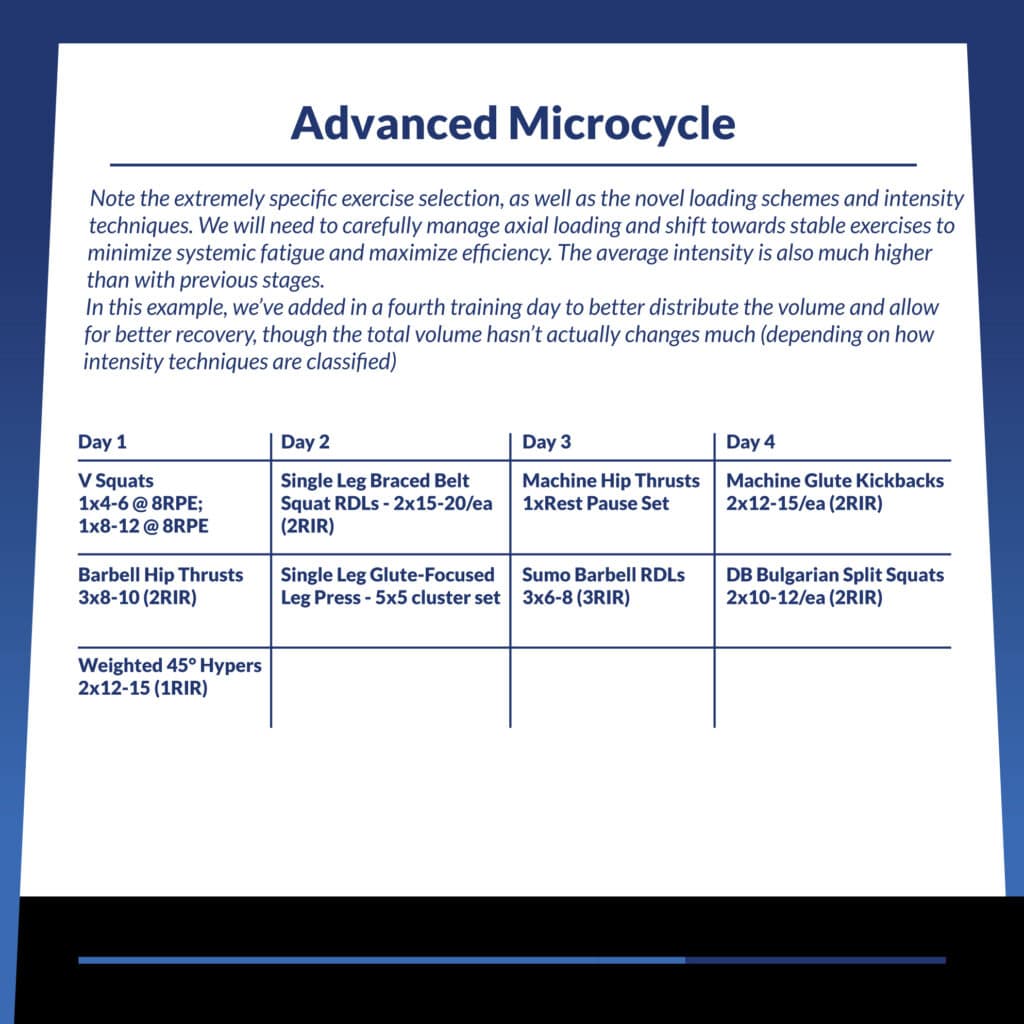

Advanced Microcycle

Note the extremely specific exercise selection, as well as the novel loading schemes and intensity techniques. We will need to carefully manage axial loading and make a broad shift towards stable exercises to minimize systemic fatigue and maximize efficiency. The average intensity is also much higher than with previous stages in order to stimulate adaptations. In this example, we’ve added in a fourth training day to better distribute the volume and allow for better recovery, though the total volume hasn’t actually changes much (depending on how you classify intensity techniques like Rest-Pause and cluster sets).

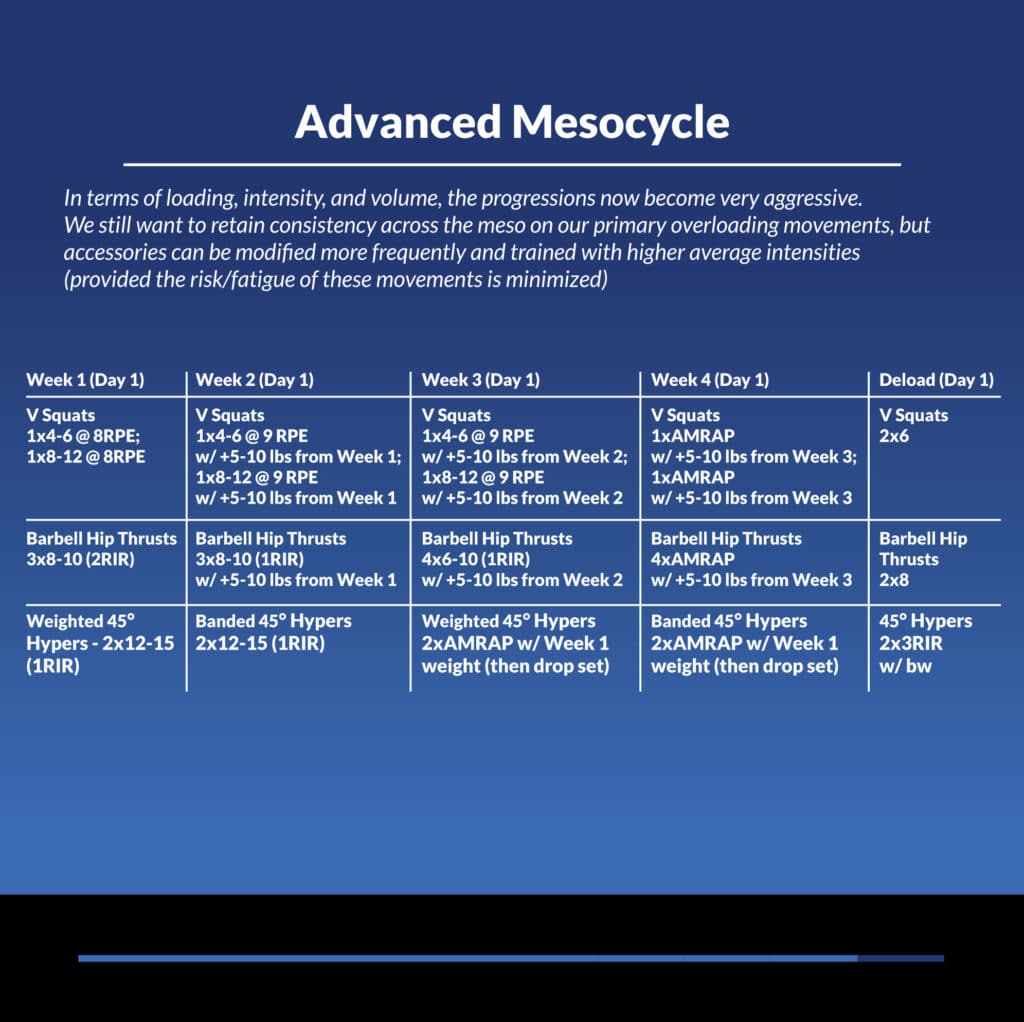

Advanced Mesocycle

In terms of loading, intensity, and volume, the progressions now become very aggressive. We still want to retain consistency across the mesocyle for our primary overloading movements, but accessories can be modified more frequently and trained with higher average intensities (provided the risk/fatigue of these movements is minimized).

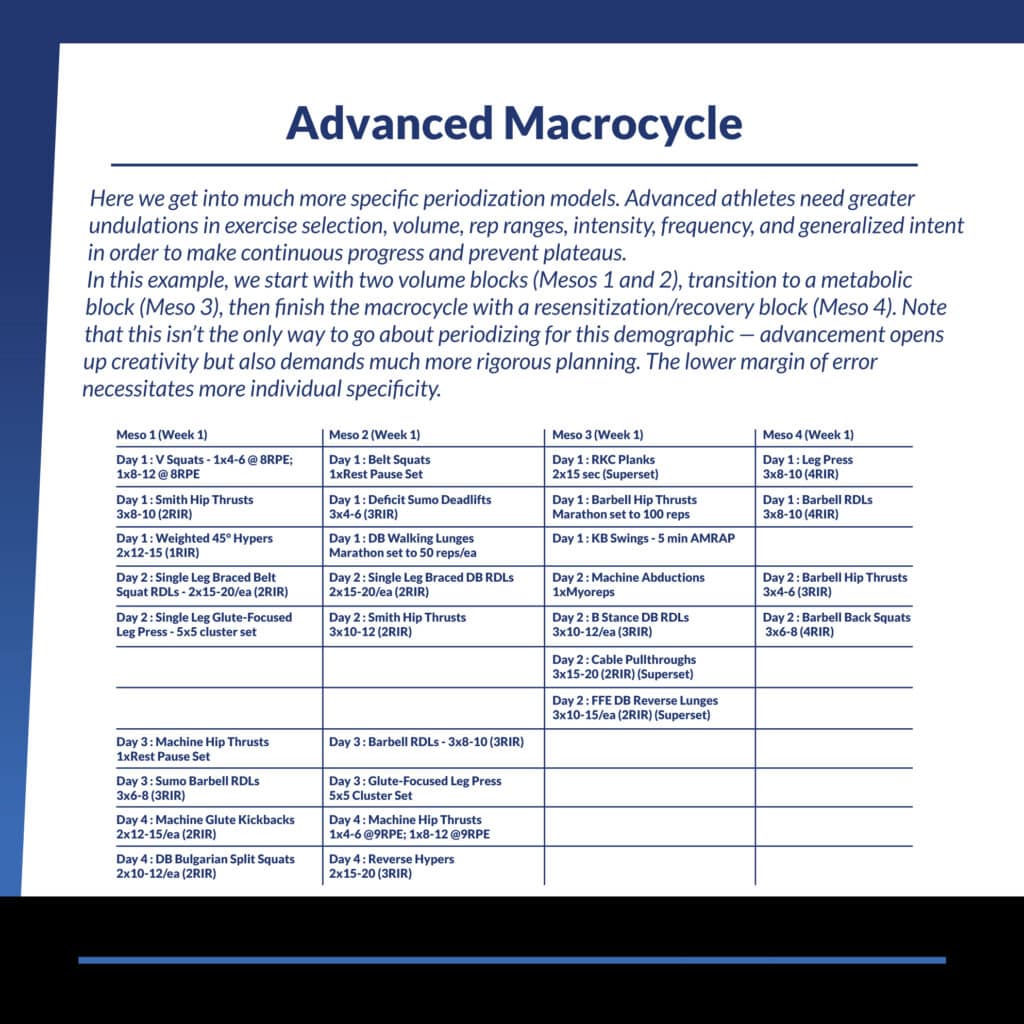

Advanced Macrocycle

Here we get into much more specific periodization models. Advanced athletes are going to need undulations in exercise selection, volume, rep ranges, intensity, frequency, and generalized intent in order to make continuous progress and prevent plateaus. In this example, we start with two volume blocks (Mesos 1 and 2), transition to a metabolic block (Meso 3), then finish the macrocycle with a resensitization/recovery block (Meso 4). Note that this isn’t the only way to go about periodizing for this demographic—advancement opens up creativity but also demands much more rigorous planning. The margin of error is low necessitating maximal individual specificity.