One thing that should be abundantly clear when analyzing exercise selection is that sexiness is not correlated with efficiency. And this maxim is pushed to its limits with the Horizontal Pull pattern.

While the pattern might not be the most glamorous, its significance in propagating muscular balance, healthy tissues, and longevity can hardly be matched.

Deep within our lizard brains, it’s instinctual to push, press and throw stuff — and we tend to favor these movements even now, often to a detriment. Inevitably, this prioritization leads to asymmetries and compensations developing over time.

How many people take as much pride in their Bent Over Row as their Bench Press?

Not many would be my guess.

Luckily then for the majority of us, it’s not too late to relax a bit on the highbrow push muscles and show a bit more love to the blue-collar pulls.

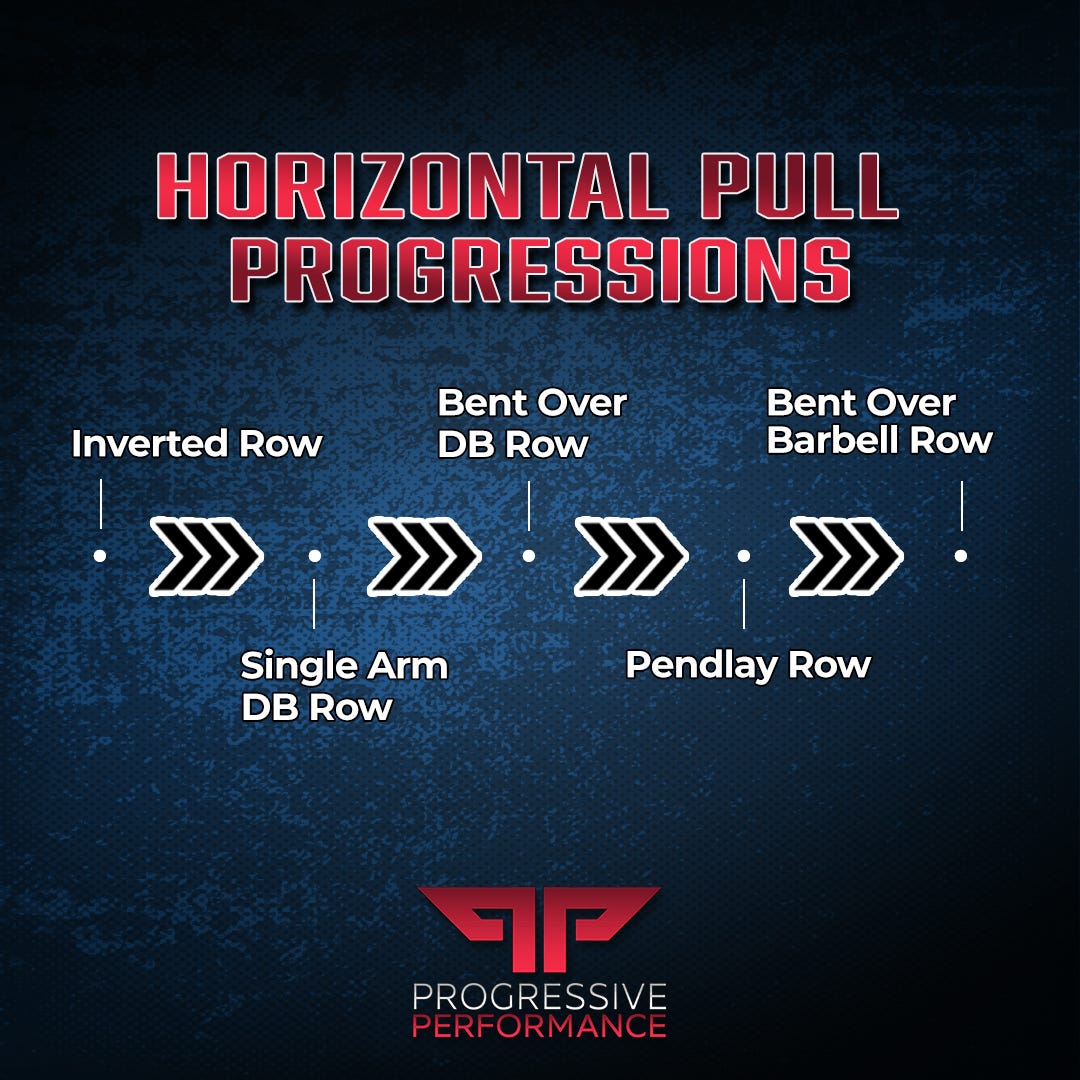

Inverted Row

Even though this represents the most regressed variation within the pattern, the Inverted Row is highly scalable and malleable to any program and trainee archetype.

The prerequisites to safely perform the movement are damn-near non-existent, which caters towards novices — but even advanced athletes can benefit from the high intensities without axial loading that Inverted Rows provide.

An additional feather-in-the-cap that separates Inverted Rows from many other Horizontal Pulls comes from the unique head-to-toe, posterior-chain rigidity that is engrained. We often think of Planks as being the standard for building core strength and rigidity but forget that this is only accounting for the anterior (front) side of the body. Inverted Rows are an inverse plank wrapped in a Horizontal Pull pattern.

*Note: Either a pronated or neutral grip would be applicable here, though we always recommend maximal freedom of movement where possible. So proficiency with TRX or Ring Inverted Rows (rather than a straight bar) would be our preference.

Single Arm DB Row

As we ascend the ranks of horpull complexity, it becomes quickly apparent that the postural endurance of the erectors, glutes and abdominals is — more often than not — the limiting factor for continued progressive overload.

Thus the unilateral, braced row (e.g. Single Arm DB Row) is lowest-hanging workaround that allows muscular coordination to develop while building strength and minimizing risk of injury (provided trunk rotation is restricted and execution is strict).

With this intermediary, we’re able to devote more attention towards the highest ROI traits (i.e. proprioception, mechanical tension, progressive overload, etc) without being artificially held back by undesired failure points. The weak links can be strategically built-up through more direct work until they are no longer the weak links for Horizontal Pull progressions.

Bent Over DB Row

When generalized functionality, strength, muscularity and longevity are the goals, it’s hard to make the case that any variation has more impact than the Bent Over DB Row.

The instability of DBs with bilateral exercises provides a hurdle with absolute load progressions (as compared to a fixed barbell), but this drawback can be offset by the benefits that come with natural joint movement and additional ROM. Now, ancillary muscle groups and support structures are heavily recruited to maintain a static “bent over” position, which requires additional levels of strength and body control.

Many row variations do a good job of growing the back muscles, building posterior chain strength, and/or engraining proper patterning, but few (if any) do these things collectively as well as the Bent Over DB Row.

Pendlay Row

Also know as “Deadstop” Barbell Rows, the Pendlay Row creates a bridge between the ever-increasing absolute load and the ever-limiting postural strength.

“Deadstop” means exactly what it sounds like — the load comes to a dead stop between reps. The ability to reset before transitioning into the next concentric allows an intermediate trainee to refine technique and push the intensity while reducing injury risk. Pendlay Rows are meant to be inherently strict, which means the ROM — and therefore, progress — can be standardized.

Flexibility and mobility variance between individuals needs to be accounted for when programming Pendlay Rows, regardless of advancement or skill level. This may necessitate adding a deficit (to increase the ROM) or elevating the weight on blocks (to decrease the ROM). Regardless of potential modifications, this variation scales well and can be applicable to a plethora of goals.

Bent Over Barbell Row

Once the pattern has been all but mastered, postural muscles strengthened, and coordination refined, the Bent Over Barbell Row is the final boss of the Horizontal Pulls.

Many muscle groups and systems must work in conjunction with one other to ensure that these can be done safely, with a load heavy enough — and intensity high enough — to stimulate adaptations.

Few movements have the potential to push development of the lats/traps/erectors further than the Bent Over Barbell Row, but it’s necessary to confront the real risk of injury that comes with using overloading weights+intensities on a movement that places so much stress on the axial skeleton. Even advanced trainees who have the skill and technical ability to perform the exercise safely will ultimately have to determine whether the marginal reward is worth the playing Russian Roulette with one’s vertebral discs.

It should be explicitly stated that muscularity and strength aren’t linearly tied to movement up or down this totem pole.

There are benefits and drawbacks inherent to each variation that aren’t predictable just by looking at its complexity; the advanced athlete may get more out of the simplicity of Inverted Rows while the beginner might catapult her progress via the increased systemic demands of a properly performed Pendlay Row. The formula isn’t exact science.

These recommendations are meant to be used as a scale to figure out how other variations can be integrated and compared. But utility can be found at all levels. Just as the Bent Over Barbell Row is the Bench Press’s ugly cousin, the Inverted Row is the forgotten, underutilized, red-headed stepbrother of the Push-Up. We know the usefulness is there, but it’s hard to see past the unsexy surface.

There is a back-of-hand adage that says pushing and pulling should be programmed in a 1:1 ratio. That is, for every set of Flat DB Presses, there should be an equal set of Bent Over DB Rows. No doubt, this is an extreme oversimplification. It’s not going to hold true for most trainees or the absolute majority of goals — but it’s still hard to refute that most programs could be improved by showing more love to rows while lusting less for presses.

One thing that will always remain true: most will continue to ignore the Horizontal Pull pattern, however, those who don’t will reap uncommon results.