One doesn’t need to be a gymnast or a lumberjack to see the relevance of being able to control heavy loads overhead. So why does it seem like the Vertical Press pattern is an afterthought compared to it’s fraternal twin, the Horizontal Press?

The simple answer: it’s harder to progress, more challenging and more uncomfortable.

The complicated answer: there are many more contributors and dependencies, with much fewer direct beneficiaries.

With Vertical Presses, the pay-offs are less obvious and less direct, which tends to have a repellant effect on a population that really likes obvious and direct results. But this says nothing of importance; in fact, whatever Vertical Presses concede in terms of aesthetics and sexiness is more than made up when it comes to functionality, strength, and badassery…

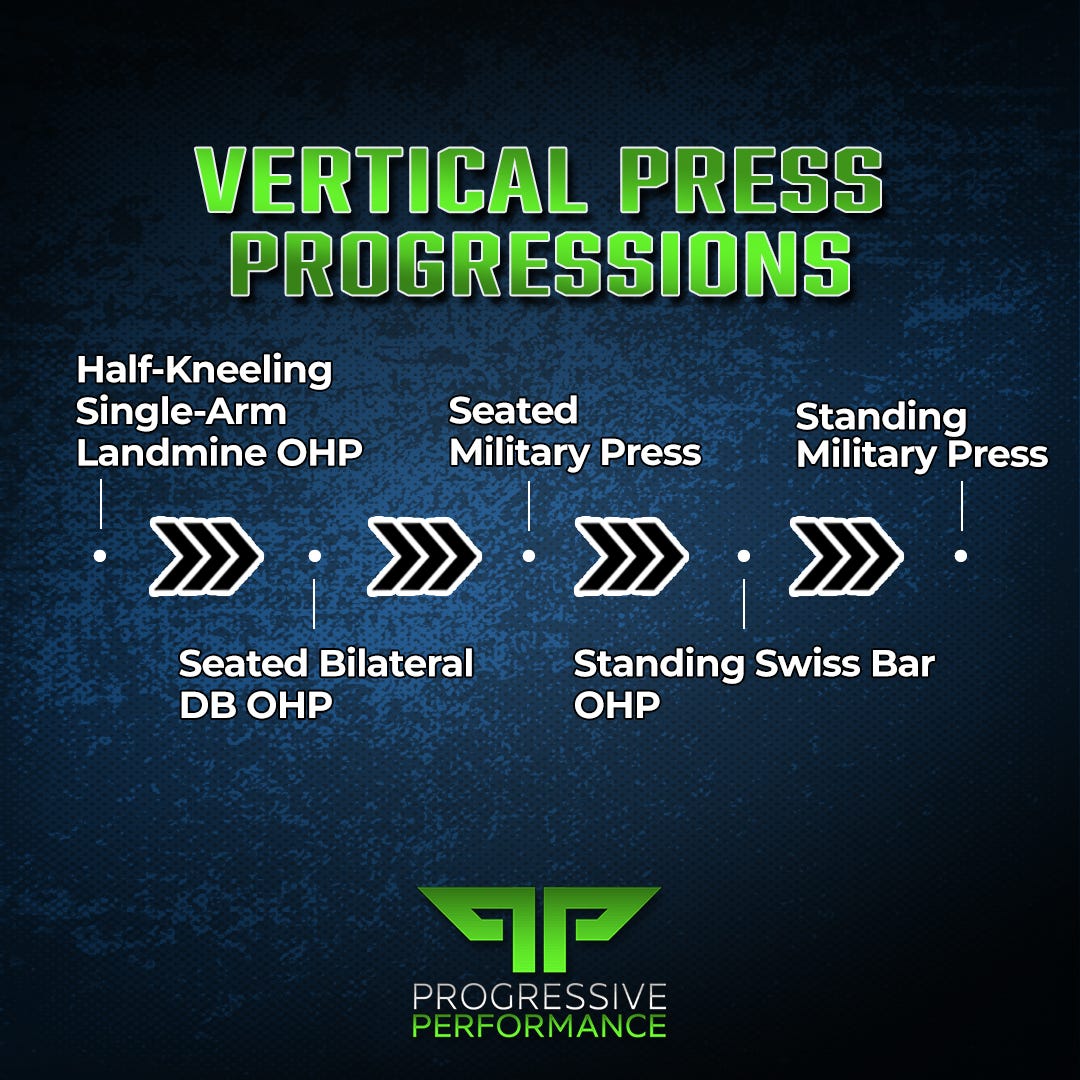

Half-Kneeling Single-Arm Landmine Press

This entry-level exercise is an ideal starting point to familiarize oneself with Vertical Pressing dynamics. However, the heavy emphasis on neutrality, positioning and stability make it less catered towards strength/hypertrophy and more favorable for engraining proper habits that will come in handy with later progressions. Even advanced trainees can benefit from this variation (especially when mobility and accumulated injuries become more restrictive), but its greatest utility comes through building an effective foundation for the movement pattern — a utility which is best utilized by novices/beginners.

Seated DB OHP

*We are assuming this movement is being performed with back support and with a semi-pronated grip, though many permutations can fall under the umbrella of “Seated DB OHP”

Progressing from HK SA Landmine Press, we have entered an entirely different universe in terms of set-up, execution, and demands. Visually, the two exercises could hardly look more different while still being considered the same pattern. Yet, a quick biomechanical analysis shows that the changes in complexity and barriers-to-entry (which is what we’re really looking at) aren’t actually that far apart on our spectrum.

We now have a shift from unilateral to bilateral (which increases the mobility and stability demands), half-kneeling to seated with back support (which actually alleviates stability requirements making the setup more favorable for loading), and neutral to pronated grip (which requires more shoulder/upper back mobility and slides the muscular emphasis from triceps/delts towards delts/upper pecs/traps).

All of this taken together provides an excellent intermediate step for Vertical Pressing that can be simultaneously overloading as well as simple to perform.

Seated Barbell OHP

Transitioning from DBs to barbell raises the bar (hehe) for technique, mobility and strength prerequisites. Unlike DBs (which allow for subtle corrections/adjustments within the pattern according to the trainee’s idiosyncrasies), the fixed barbell is less forgiving, demanding a strong/stable upper back to be able to control the entire ROM (as opposed to being controlled by the exercise).

Though Seated Barbell OHP was a staple of bygone eras, it’s significantly less common to see programmed these days. The main reason for this (though there are many contributing factors) is that the increased demands/limitations that come with the introduction of the barbell tend to offset most increases in productive outcomes. Though it’s important to note that this can be rectified through “machination” — in other words, fixing the plane of movement (e.g. Smith machine).

Standing Swiss Bar OHP

Moving from seated to a standing position (and removing the back support) significantly increases the complexity of the movement. The Swiss Bar’s neutral grip keeps the upper arms more adducted, alleviating demands on shoulder mobility as well as engaging ancillary muscles (e.g. the triceps) to help out the delts.

The shift to a neutral grip enables one to manage the complexity jump in stages, but the progression has now reached the point of necessitating synchronization from head-to-toe (HK SA Landmine Presses did as well but in a much less rigorous way) — any weak links in the chain or technical mishaps can quickly lead to injury. Hence, core strength, coordination, proprioception, and technique are paramount in ways that they haven’t been up to this point.

Standing Barbell OHP

The tip of the Vertical Press pyramid, the Standing Barbell OHP requires mastery over every facet of the pattern. One can say many of the same things about this variation as was already established with the Swiss Bar alternative, but the straight barbell is a complexity-raising variable unto itself. Pronating the grip naturally abducts the elbows, placing increased demands on shoulder mobility and upper back strength.

Given the highly refined prerequisites of this exercise, it’s rare to witness the Standing Barbell OHP performed in a manner sufficient to overload the actual Vertical Press pattern. More often than not, subordinate limitations steal the show — which is why the Standing Barbell OHP should be programmed extremely specifically (and with a deep understanding of the trainee’s strengths/weaknesses) if it’s to be utilized productively.

When incorporating any Vertical Press variant, the underlying intent should be explicit — whether it’s strength, hypertrophy, stability, or simply for the sake of increased variation.

Given the shoulder joint’s hyper-mobility and the complexity associated with the higher-level variations, trainees (and coaches) must continually weigh goals against potential risks. Even minor miscalculations with respect to one’s placement along the progression gradient can have serious consequences.

Despite not being a focal point of this article, machines can offer standardization, safety and substantial overloading potential, while eliminating many of the prerequisites that plagued their free-weight counterparts. Therefor, it’s in one’s interest to consider and evaluate how machine-based Vertical Presses can be effectively integrated into the progression/regression paradigm.